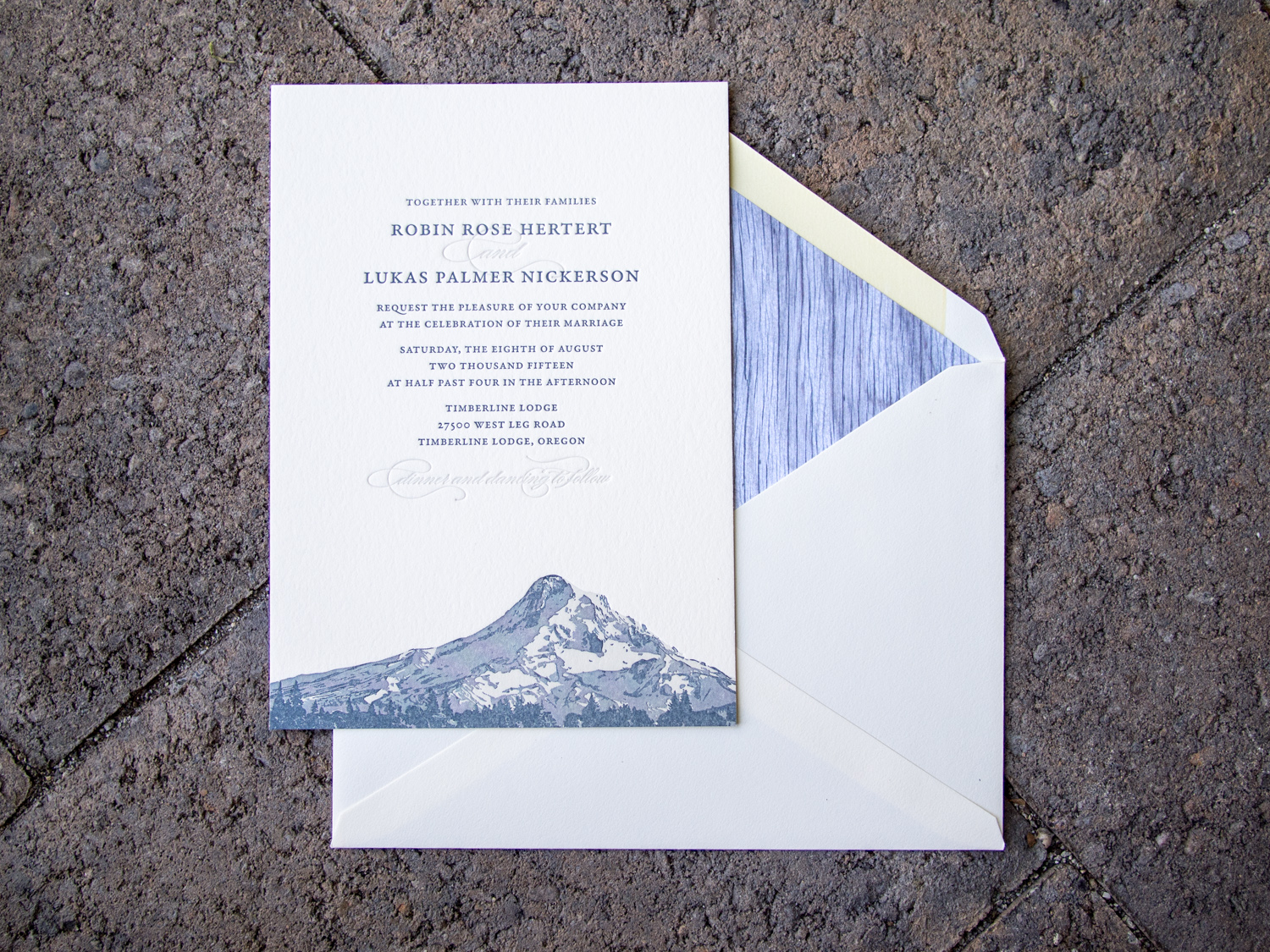

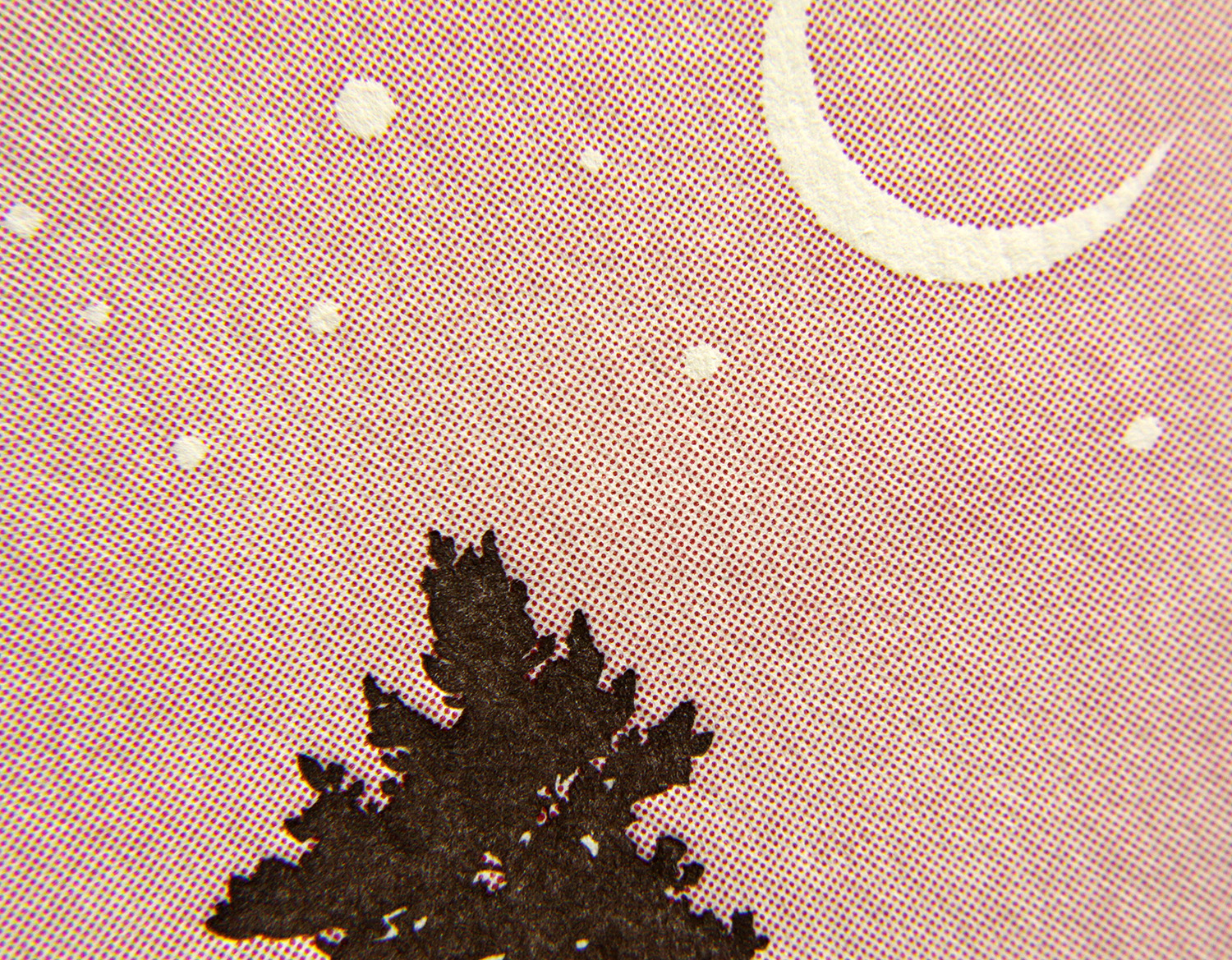

We all learned in grade school that mixing colors together creates new colors. Halftone screens don't actually mix the colors, but when layered on top of each other, they create the appearance of blended colors, so the artwork looks to have a greater color range than it actually does. It's like a technique used by Impressionist painters (and more specifically, pointillist painters) — laying down adjacent dabs of color, leaving the "mixing" to occur in the eye of the viewer.

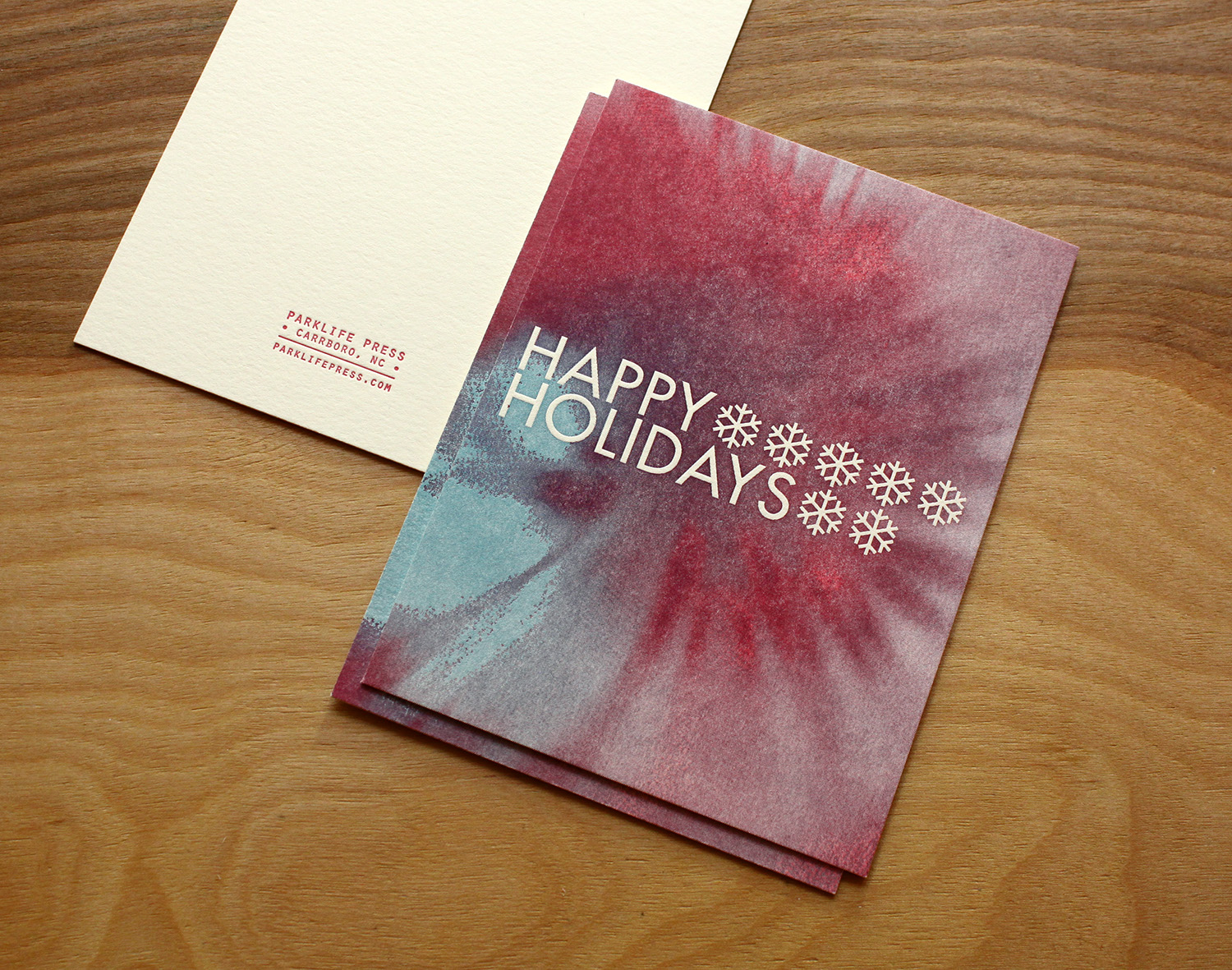

Below, blue and red ink screens create a swirl of blue, red and purple shades, suggesting a tie-dye effect.